The 14th Venice Biennale of Architecture, Elements of Architecture brought a different tone to the world’s premiere architecture exhibition. Carrying the theme “Fundamentals,” the Biennale had an aim to be, in the words of curator Rem Koolhaas, “about architecture, not architects.” A focus on the components of Architecture come together in exhibitions and mammoth book series–a collaboration between Koolhaas’s research studio AMO and the Harvard GSD. I spent the summer of 2013 at the Rotterdam office participating as a cog in the behemoth project.

The 14th Venice Biennale of Architecture, Elements of Architecture brought a different tone to the world’s premiere architecture exhibition. Carrying the theme “Fundamentals,” the Biennale had an aim to be, in the words of curator Rem Koolhaas, “about architecture, not architects.” A focus on the components of Architecture come together in exhibitions and mammoth book series–a collaboration between Koolhaas’s research studio AMO and the Harvard GSD. I spent the summer of 2013 at the Rotterdam office participating as a cog in the behemoth project.

- The Floor Volume

Harvard GSD sent two studios–in 2012 and 2013–with 12 students each to Rotterdam for the development of the Biennale. In Rotterdam over the summer of 2013, I worked on the editing team of the Elements project. After the opening this June, Elizabeth MacWillie (MDesS/MAUD 2014) walked me through the book process and exhibition in the Central Pavilion of the Venice Biennale, open until November 23, 2014. MacWillie and some of the participants in the Harvard-AMO Rotterdam studio elected to stay in Rotterdam after the studios finished to continue work. In addition to MacWillie and myself, the Elements editing team included GSD alumnus Nicholas Potts (MAUD ’13), Tiffany Obser (MArch ’14), Annie Wang (MArch ’15), and Eric Williams (MArch II ’15)

Elements of Architecture dug deep into what are considered since antiquity to be the fundamentals of which buildings are composed–door, roof, wall, floor, fireplace, etc. Modernity seeps in with some unexpected components—the elevator, escalator, balcony, and, a surprisingly deadpan take on the toilet.

MacWillie described the research approach. “When we began the studio, editor-in-chief James Westcott and our other instructors emphasized developing a narrative for each element. Each spread we pinned up was meant to be an argument that was a combination of images and some text to investigate ‘what were the moments of true transformation in the elements?’ Rem Koolhaas would emphasize to us to form ‘short, pithy captions’ to accompany the images. It was important to not rely solely on text to build up the argument. Having images, explicitly labeled with their dates, and placed on a page in relation to each other with short, very dense captions, in order to build up an argument—this was a new process of researching and writing for me.” Aiding the craft of the argument, Dutch graphic designer Irma Boom collaborated with AMO to specialize the book layouts specific to each element.

Harvard students collaborated in small groups with scholars and researchers to tackle a few of the Elements chapters. MacWillie elaborates, “Having multiple eyes from different cultural perspectives helped to make each chapter more full. It’s a global perspective, but also a personal one.” The elevator includes a story from studio participant See Jia Ho (MArch I ’15). Growing up in Singapore, a land of high-rise housing enabled by the elevator, she relays childhood memories. In the elevator void deck, an unoccupied ground space in many Singapore apartment towers, she and her friends would play ball.

The emphasis on the global and multicultural infused my own work on Elements. During my 3-month post in Rotterdam in summer 2013, Westcott assigned me to work on the etymologies for each element, given my training in Romance languages and Latin. As etymology is the study of the origin of words and how they evolve, it wasn’t so much a matter of invention, but rather corralling a tremendous amount of raw material, such as definitions and how the words are used within literary and spoken context. Westcott and I worked closely to figure out how to structure the etymologies. The formidable Oxford English Dictionary was a good place to start, as English is a melting pot of words with shared roots spanning Latin, Greek, German, Dutch, French and the other Romance languages. Yet for other languages, such as Swahili, Russian, Mandarin, Japanese, we reached out to native speakers to mine through dictionaries or relay how words appear in context.

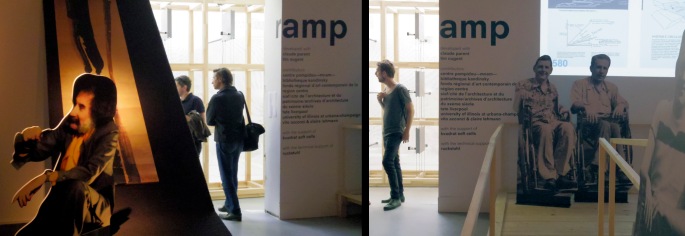

- The Ramp room illustrates the work and approaches of Tim Nugent and Claude Parent who devoted their lifetimes to the study and design of the ramp, with extremely unique outcomes. Nugent declared the universal necessity of adapting the ramp for every type of body, enabling access to physically disabled people. Claude Parent, father of the “The Oblique Function,” preferred steep ramps.

The etymology project revealed a dense web of meanings beyond generic understandings. For example, looking at the word “window,” the etymology demonstrates how the word descended from eagduru, meaning eye-door in Old English. Roots in Greek underscore the window’s role as producing light, whereas Latin establishes the role of the window as transmitting air into a room. Well, what is its role, to let in light or air? In Swahili, mwanganazi means literally to be in view. Other cultures implicate the window in the gaze, adding a gendered slant to the window. A Spanish dictionary dating to 1706 includes a phrase translated to “whores at the window”—implying that honest women ought not spend their time at the window, as they might be seen. The study of language illuminated cultural understandings and uncovered glacial shifts in mindsets about the elements.

For MacWillie, the research process also yielded unexpected outcomes. “Starting out, I worked on the balcony,” MacWillie explains. “I wasn’t sure how to get excited about it at first. By the end of the project, I felt pretty attached to and enthralled by the balcony. Part of this captivation came from how, by looking at the elements at that scale, they all took on a certain social, political or human relevance that I hadn’t necessarily noticed before beginning the project.” The Balcony chapter, for example, narrates how the balcony has been coopted by public figures from fascist dictators to celebrities. “Elements includes the tangible ways that each element has influenced people and the way that we live in architecture.”

Take for instance Friedrich Mielke, German scalalogist–a person dedicated to the study of stairs. From a lifetime devoted to “rise over run,” his drawings, artifacts and research are on view, as well as a video excerpt from his interview with the AMO team, where he is on the verge of tears during one impassioned explication of stairs.

While some criticism of Elements has been about the authoritarian tone of the exhibition (“Why these elements—should we believe it?” Or: “Why is Light left out?”), I experienced quite the contrary. If anything, Elements of Architecture pierced common narratives of architecture’s evolution to include a range of voices either forgotten, never heard, or never invited into the official “architecture-speak.” MacWillie reported her shift in perspective, “Thinking about architecture in terms of the elements has enabled me to see a human aspect and remember an excitement for architecture that I had forgotten.”

Part of the Elements of Architecture, and the greater Fundamentals project at the Venice Biennale is to take stock and question the foundations of contemporary architectural discourse. Koolhaas states, “This retrospective will generate a fresh understanding of the richness of architecture’s fundamental repertoire, apparently so exhausted today.” Indeed. While at once there’s an insistence on studying objects, at the same time choreographed artifacts and narratives form an unexpected “human element” to the Elements project. Life inevitably seeps in.